Most “music creation” problems are not really about music. They are about requirements.

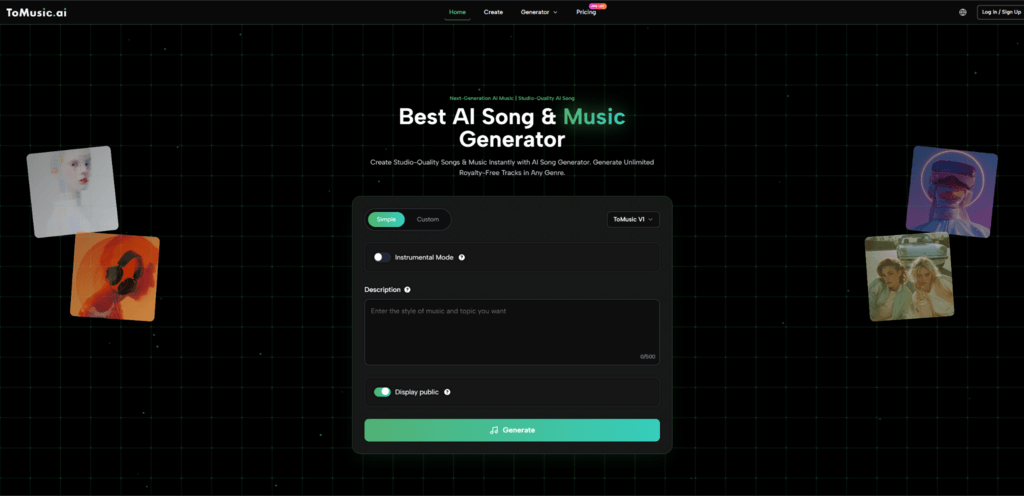

You need a track that supports a voiceover without fighting it. Or a hook that arrives fast enough for short-form. Or a calm bed that can loop without becoming annoying. When I approached an Text to Music AI workflow with that mindset—treating music like a set of product requirements rather than a burst of inspiration—the results became easier to control, easier to compare, and far less dependent on luck.

This article shares that framework. It is not a promise of effortless perfection. It is a method for turning “I want something cool” into “I can explain why this version works.”

Start With an Audio Spec, Not a Genre

A genre label is a vibe. An audio spec is a decision.

What an audio spec includes

- Use case: reel, ad, tutorial, podcast intro, product page, full song

- Primary constraint: voiceover-friendly, hook-fast, loopable, cinematic build

- Energy curve: steady, slow build, peak-and-release, immediate hook

- Density target: minimal, medium, full

- Vocal intent: none, light, prominent

- Avoid list: one or two hard “no” items (busy hi-hats, heavy distortion, big drops, etc.)

In my tests, the moment I wrote an avoid list, the output improved—not because the tool suddenly became smarter, but because my direction became clearer.

Turn Your Audio Spec Into a “Prompt Contract”

Instead of writing long poetic prompts, I use a short contract that the generator can interpret consistently.

A reliable prompt contract format

- Length target (15s / 30s / 60s / full track)

- One genre anchor (avoid stacking multiple genres)

- Two moods only (three max)

- Energy/tempo guidance (mid-tempo, fast, or BPM)

- Two texture cues (instruments or production traits)

- Vocal intent (optional)

- Avoid list (one hard “no”)

Example

“30–45s, modern pop, bright + confident, hook in first 10 seconds, clean drums + warm bass, light vocals, avoid heavy distortion.”

This structure is intentionally boring. That is why it works.

Use a Scorecard: Make the Tool Compete With Itself

The fastest way to lose time is generating endlessly without a way to judge.

Instead, generate three candidates and score them. The goal is not to find “the best song.” The goal is to find the best match to your spec.

A simple scorecard I used

- Fit (0–5): does it match the content’s emotional target?

- Clarity (0–5): does the arrangement feel clean or crowded?

- Movement (0–5): does it evolve in the right way?

- Usability (0–5): would I actually place this under my edit today?

Once you score, you stop arguing with your own taste. You can say, “Take B is clearer, but Take A moves better. I want clarity, so I will reduce density.”

Iteration Rule: Change One Variable Only

If you rewrite everything at once, you cannot learn what helped.

My single-variable iteration list

- Make it slower/faster

- Make it warmer/darker

- Make it more minimal/more full

- Make vocals lighter/more present

- Swap one texture cue (guitar → synth, tight drums → soft drums)

When I followed this rule, improvement felt predictable. When I ignored it, outputs bounced around and I ended up chasing my tail.

Where Model Choice Fits (Without Turning It Into a Ritual)

Many generators offer multiple model versions. The useful way to think about this is: different models can interpret the same brief differently.

How I used model switching

- If the brief felt correct but the take felt messy, I tried another model before rewriting the contract.

- If I already had the direction and wanted a more “finished” feel, I switched models after the spec was locked.

This is not magic. It is just a practical lever for changing arrangement behavior without rewriting your whole idea.

Comparison Table: Requirement-Based Workflow vs Common Alternatives

Here is what changes when you treat music like a spec.

| Comparison Item | AI Music Generator | Stock Music Search | Traditional DAW Production |

| Starting point | Audio spec + prompt contract | Tags + browsing | Skill + time |

| Speed to 3 viable options | Fast | Medium | Slow |

| Ability to match your edit timing | High | Low–Medium | Very High |

| Uniqueness | Medium–High | Low–Medium | High |

| Control | Medium (brief + iteration) | Low | Very High |

| Best for | frequent publishing, tight deadlines | safe background choices | maximum polish |

If you publish often, the advantage is not just originality. It is decision velocity.

Limitations That Make This Feel Real

If you go in expecting perfection on the first try, you will be disappointed. In my testing mindset, variability is part of the cost of speed.

What can vary

- A prompt can produce very different outcomes across attempts.

- Vocals can be less clear when lyrics are dense or phrasing is long.

- Overloaded prompts often create “indecisive” arrangements.

What helped when results missed

- Reduce to one genre anchor.

- Cut moods to two.

- Remove one texture cue.

- Regenerate three candidates, then score again.

- Adjust one variable only.

That turns randomness into a controlled feedback loop.

A Note on Rights and the Wider Context

AI-generated music sits inside a broader industry conversation about licensing, rights, and compensation. You do not need to solve that debate to experiment responsibly, but it is worth staying aware—especially if your work is commercial and you want predictable risk boundaries.

My practical approach is simple: treat licensing and usage terms as part of your requirements, just like tempo and mood.

A 10–15 Minute Session Template

- Write an audio spec (use case, constraint, energy curve, density, avoid list).

- Convert it into a prompt contract (short and structured).

- Generate three candidates.

- Score them (fit, clarity, movement, usability).

- Pick the best and change one variable only.

- Test under your real edit before generating again.

Used this way, a text-to-music workflow stops feeling like gambling for a great take—and starts feeling like directing a process that reliably gets you to “good enough to ship,” with a clear path to improve.

Chase Ortiz is part of the team at PaigeSimple, where he takes care of all the advertising requests. With a sharp eye for detail, Chase makes sure every advertising opportunity is handled smoothly, helping the site grow and reach more people. His ability to manage these tasks efficiently makes him an important part of the team.